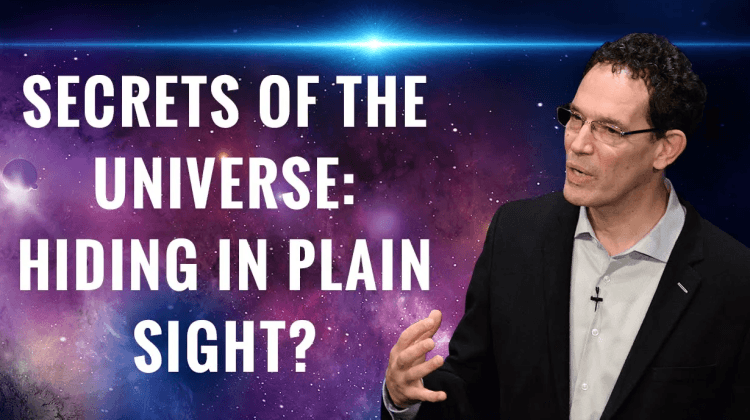

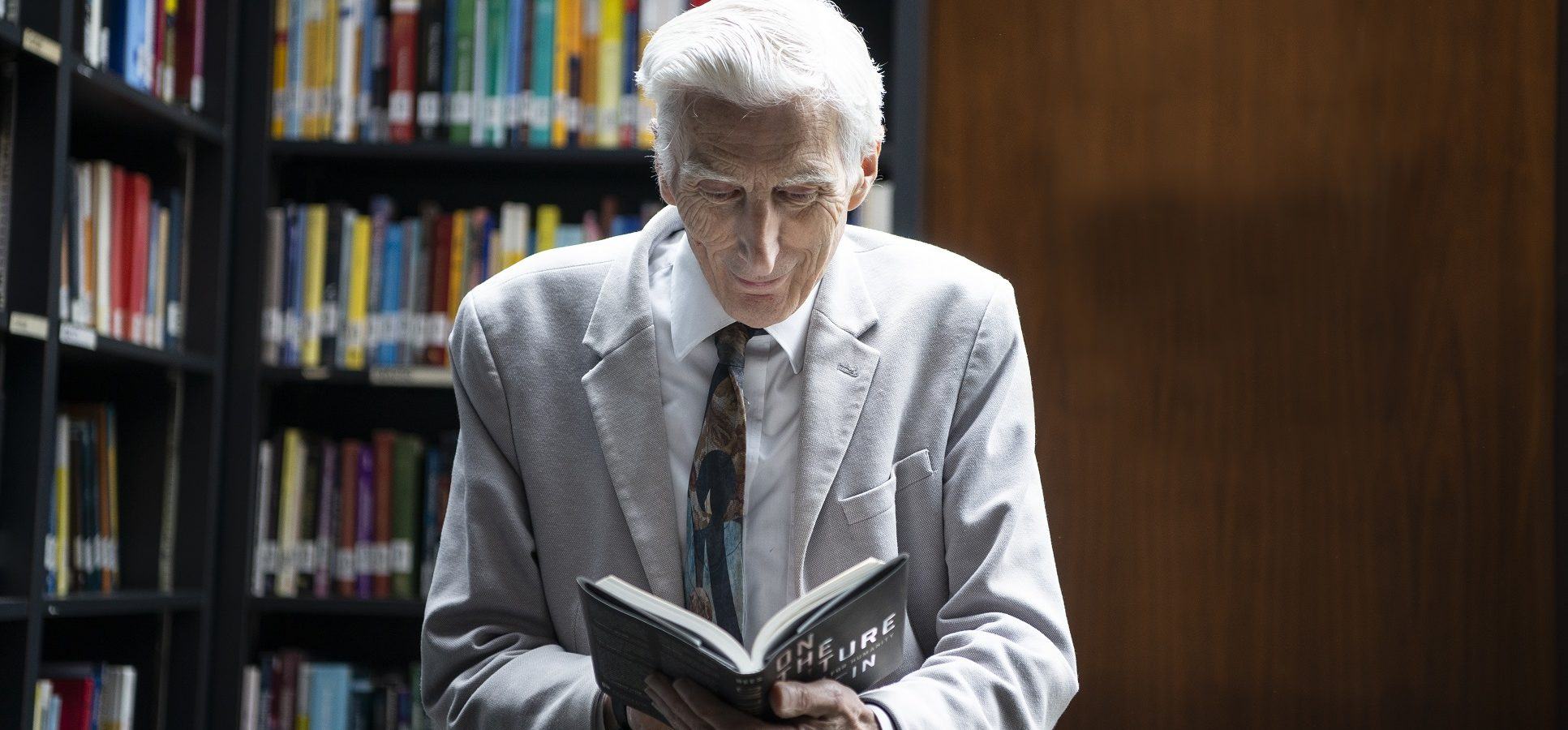

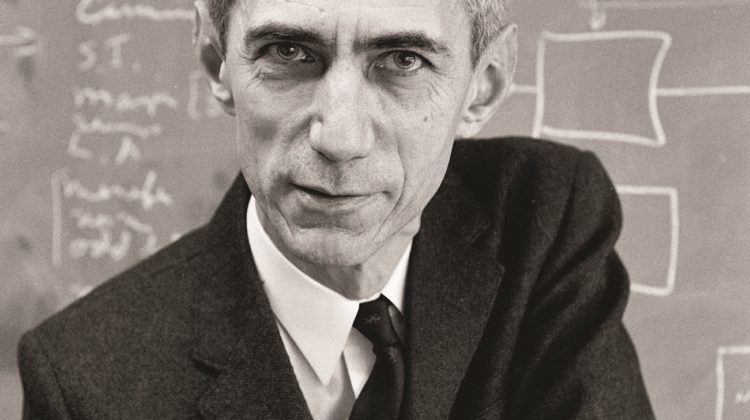

Sir Martin Rees on stars, science, and signs of life

In his latest book, UK Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees explores how humanity’s rapid technological advances are threatening – and may ultimately vouchsafe – our survival as a species. He sat down with Inside the Perimeter to discuss why he believes science provides our clearest glimpse into the future.