Take a self-guided tour from quantum to cosmos!

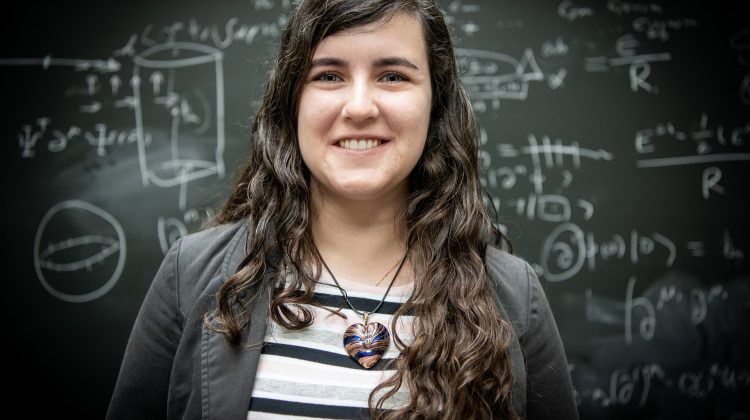

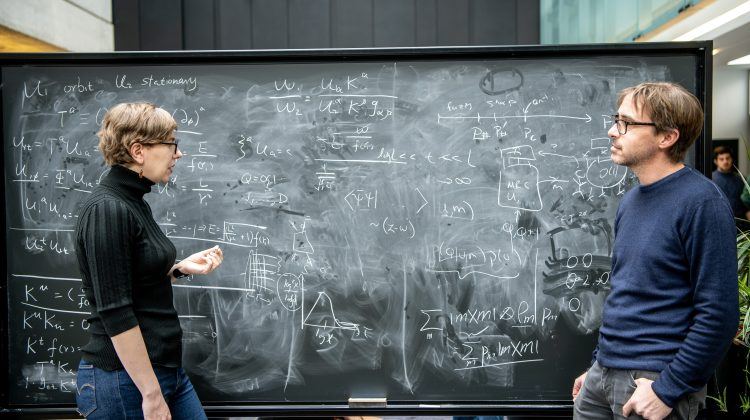

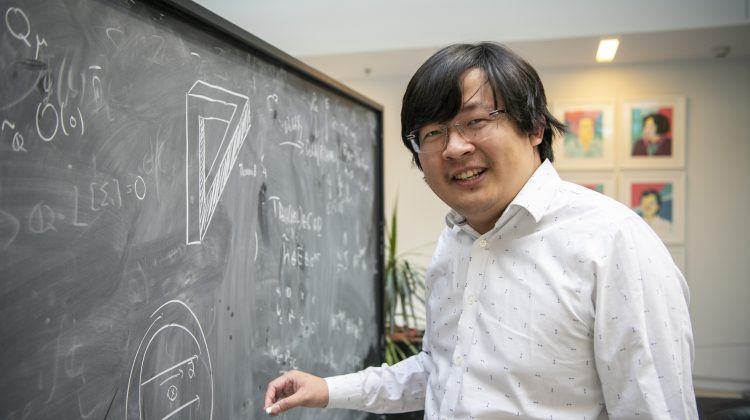

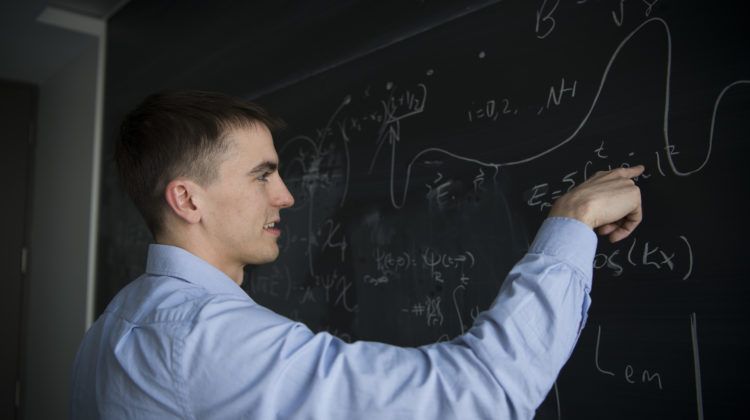

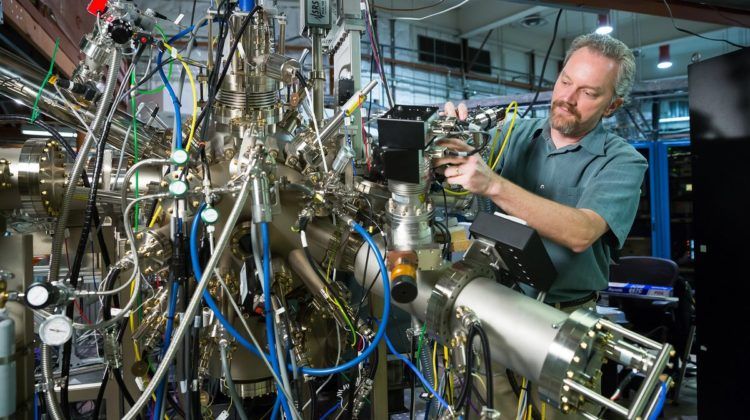

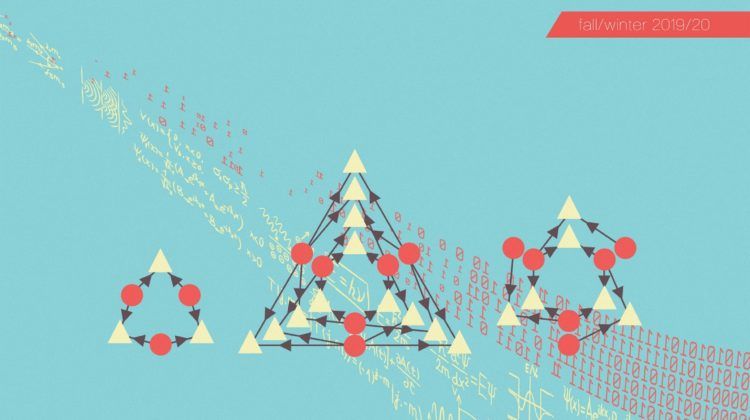

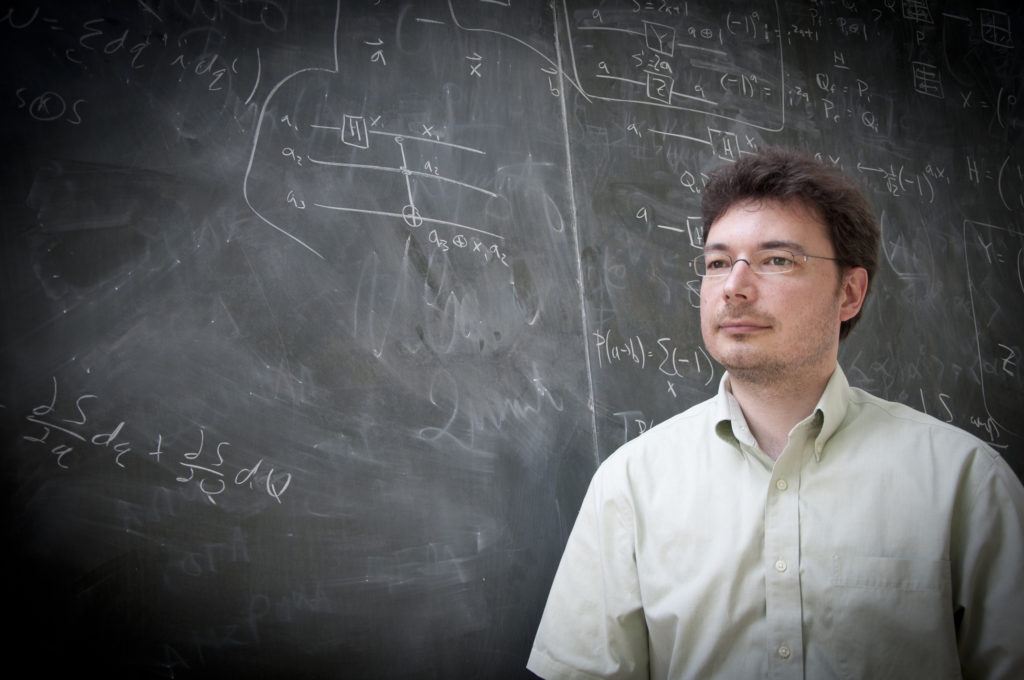

Theoretical physicists — traditionally seen as low-tech devotees of blackboards, chalk, and scribbled equations — have increasingly been exploring the world of software design and production. And while coding might seem like a departure from fundamental research, many Perimeter physicists have found that their software side hustle actually accelerates scientific progress.

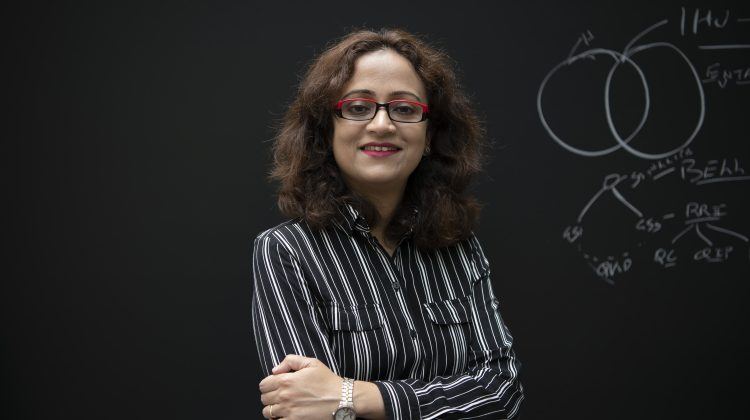

“Theoretical physics is progressing to be a kind of human-computer collaboration,” says Perimeter Associate Faculty member Roger Melko, who heads the Perimeter Institute Quantum Intelligence Lab. Some of their results are proving sufficiently useful and versatile to attract interest from the broader scientific community and industry.

Expanding beyond a user base of one

Writing a bit of code here and there isn’t all that unusual for a physicist. Often, off-the-shelf software isn’t optimized or suitable for the problems that arise working at the cutting edge of science. Nearly every grad student, postdoc, or professor has spent days (or months) building a custom tool to tackle a specific research problem.

But making the shift from hyper-specialized one-off code to software development requires a change in mindset. It’s not always easy to consider how your code might be used more generally.

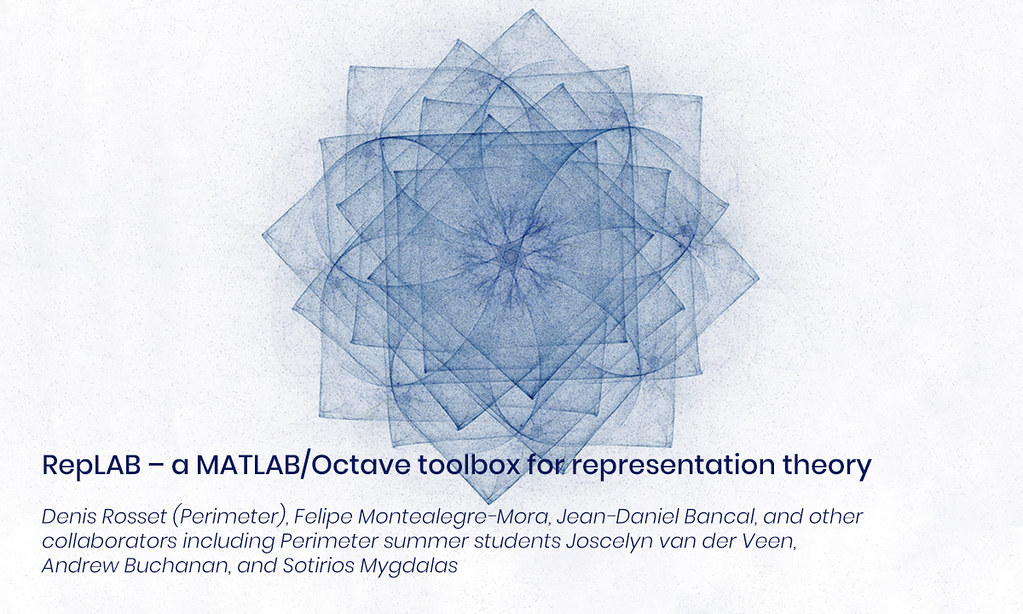

“You don’t know how the user will use your product,” says Denis Rosset, a former Perimeter postdoctoral researcher who has released several software packages. “You have to make sure that every possible combination of features will work together.”

Providing flexibility for broad use involves clearing several hurdles, notes William Cunningham, who recently wrapped up his postdoctoral research at Perimeter. “When you optimize for a specific computer or supercomputer, it’s very particular to your own workspace,” he says. “If you want something that can work on a computer that you’ve never used before, you face all sorts of challenges.”

There’s also the matter of keeping everything current as technology improves. “You have to keep up with the latest hardware,” says Cunningham. “Something that was good five years ago – if you don’t do anything to it, it isn’t going to be as good today.”

An open community

Many physicists choose to make their software open source, which means anyone can get under the hood and adapt, upgrade, or expand it. This can lighten the load for handling updates and bug fixes. It also contributes to a culture of openness and exchange.

That culture of collaboration can help push science forward, says Erik Schnetter, Perimeter’s Research Technologies Group Lead.

“Handing out code doesn’t give a free lunch to others, because learning a code takes time,” he says. “You get collaborators. If a large number of people work on the code, they help improve it, and that grows the field.”

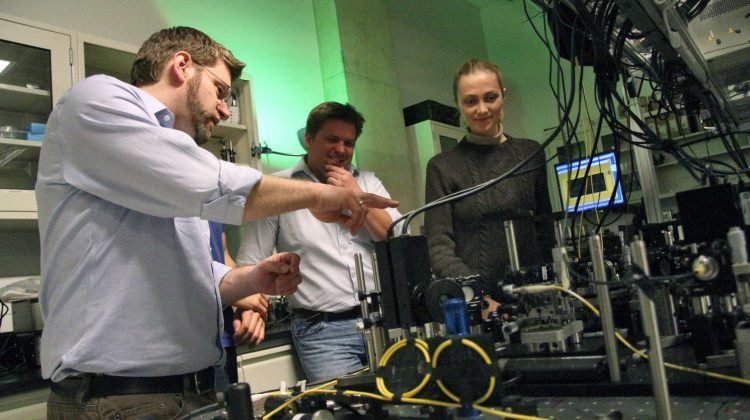

At Perimeter, quantum computing provides a prime example of the interplay between open software and open science, because the hardware and the software are being developed hand-in-hand.

“We’re using software to manipulate, validate, control, and characterize quantum devices, which are basically science experiments,” Melko says.

What’s more, he adds, open software can be an exceptional educational resource for students: “Open source plays a big role because you can see how the sausage is made – you get right in there and see all the code and all of the revisions.”

Professional recognition

“Programming is a very marketable skill,” Cunningham says. “It provides students with a better foundation for seeking jobs in the future.”

Despite that, it can be tough for scientists to get recognition for their computational contributions. The impact of a scientific paper is measured by citation count, but the software has no straightforward analog. Cunningham thinks it’s time for that to change.

“I think it would be nice if it were more well recognized, because it truly is a job in itself aside from research,” he says. “These are the types of tools that can accelerate research by a factor of 100 or 1,000 – not only because you can take more data and get much more accurate results, but you can also answer different types of questions.”

Schnetter says the problem can run deeper than a lack of recognition. With some hiring committees, he says, “If they see that you’ve published a code, that almost counts negatively against you. They see someone who spends way too much time with the details instead of going after the big ideas.

“But in terms of community service, it’s important to release things,” he says.

“What academia could do – but it would require a cultural change – is to have engineers on site that would help people package the software for public consumption,” Rosset says.

Perimeter is working to promote a culture where programming becomes a recognized aspect of doing groundbreaking science. Schnetter and computational scientist Dustin Lang offer courses, collaborate, and provide general computational support to the Institute’s researchers.

Rosset says the support and freedom he found at Perimeter made it the ideal place to grow RepLAB, a flexible suite of mathematical software tools.

Cunningham agrees that Perimeter’s support for physicist codes is unusual and substantial. “The resources are really first-class. I’ve really found few limitations in what I’ve been able to do,” he says.

Spotlight on Perimeter’s scientific computing tools

Perimeter researchers have produced many tools that contribute to their fields and beyond. Click through the gallery for a look at just a few.

A Simons Emmy Noether Fellowship has given experimental physicist Urbasi Sinha the opportunity to collaborate with theorists at Perimeter.

Perimeter graduate student helps speed up quantum computing for practical problems

‘Magic’ has a technical meaning in quantum theory, and Perimeter’s Timothy Hsieh and collaborators have found a huge source of it.