Survey validation results from DESI excite scientists studying dark energy

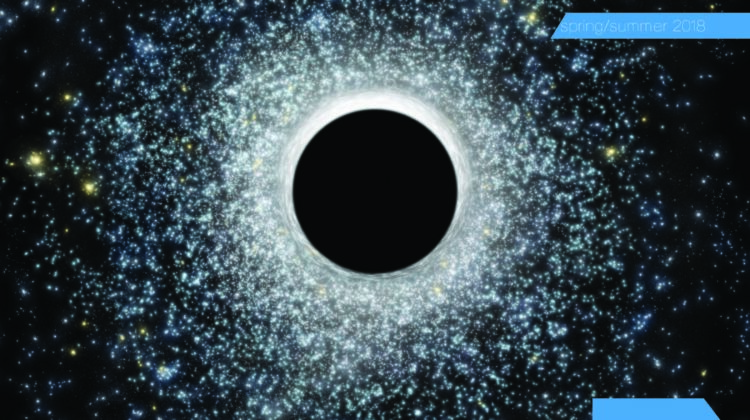

When describing dark energy, calling it a mystery is an understatement.

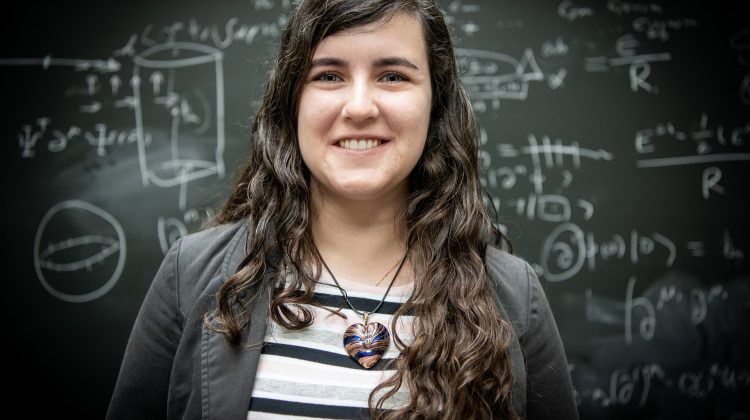

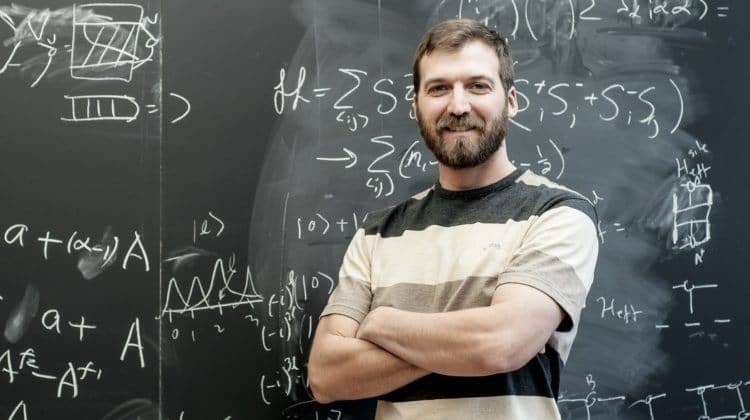

“People say it is the biggest cosmological mystery, and it is, but it is also super-weird. There is nothing else like it in the universe to relate it to,” says Perimeter computational scientist Dustin Lang.

Dark energy is something that is causing the entire universe to expand — and not just pushing spacetime itself apart but doing so at a faster and faster rate.

What is it? We have no idea.

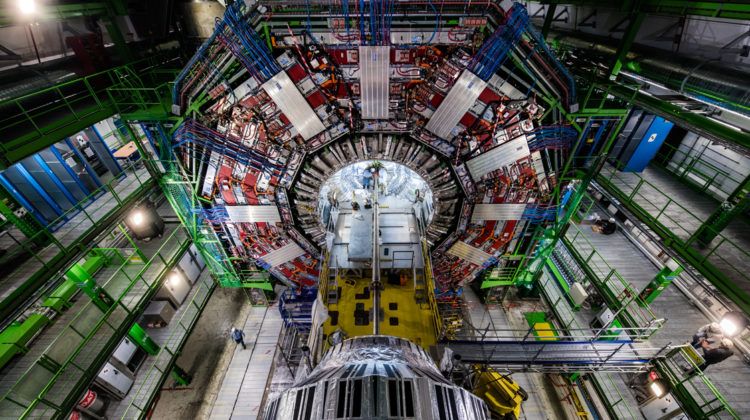

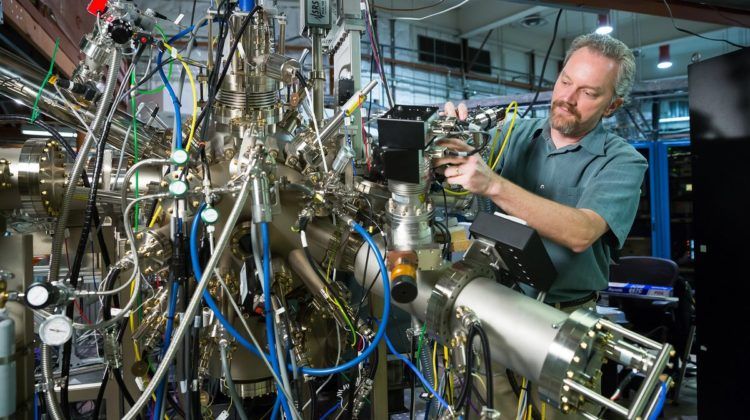

But now, a sophisticated piece of equipment, the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) that sits atop the Nicholas U. Mayall 4-meter telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, will provide new insights.

This week, DESI released data from the experiment’s “survey validation” stage. It’s an initial batch of publicly released data, that comes from 2,480 exposures taken over six months in 2020 and 2021, between turning the instrument on and beginning the official science run. It includes nearly 2 million objects for researchers to explore.

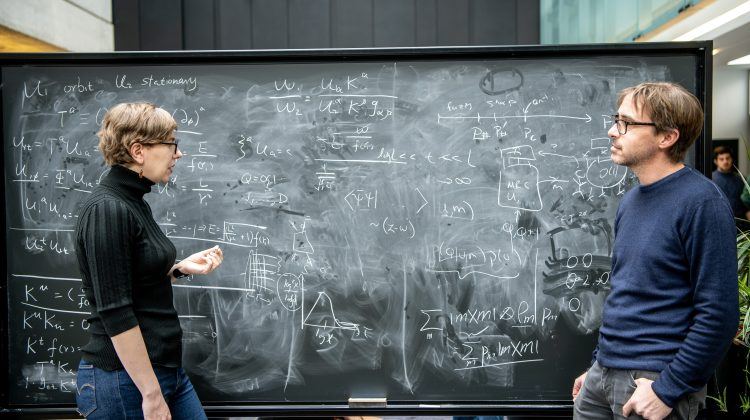

That’s just a fraction of the data that DESI has already collected. Even more exciting announcements will come from the much bigger data sets that scientists such as Will Percival, a research associate faculty member at Perimeter and director of the Waterloo Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Waterloo, are now studying.

Ultimately, DESI will map more than 40 million galaxies, quasars and stars.

But this initial release marks the opening chapter for the data that will be used to build the 3D maps of the universe, possibly leading to new theories about dark energy and what’s driving it.

It’s a monumental achievement on the part of the international DESI team of “builders,” including Percival and Lang.

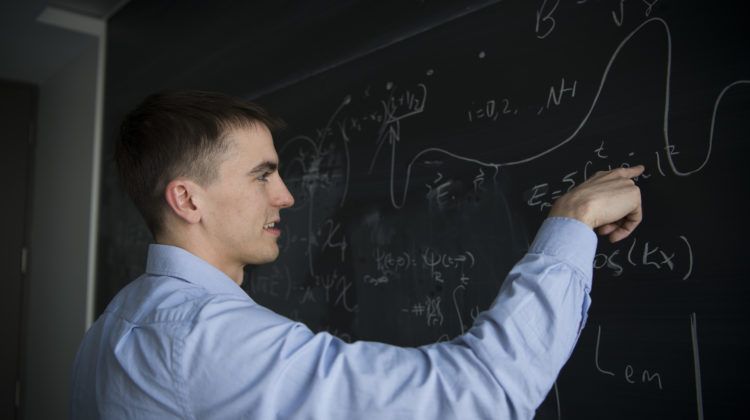

The data from the survey validation phase — when scientists were checking how long it took to observe galaxies of different brightness and validating the selection of stars and galaxies to observe — proves that DESI is not just working tremendously well as an instrument, “but also that what we wanted to observe matches what we expected it to be like,” Percival says.

That is the fruit of years of labour. Lang and Percival have been working on DESI for at least a decade. Prior to that, they also worked on the DESI precursors — the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and the Extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (eBOSS) experiment.

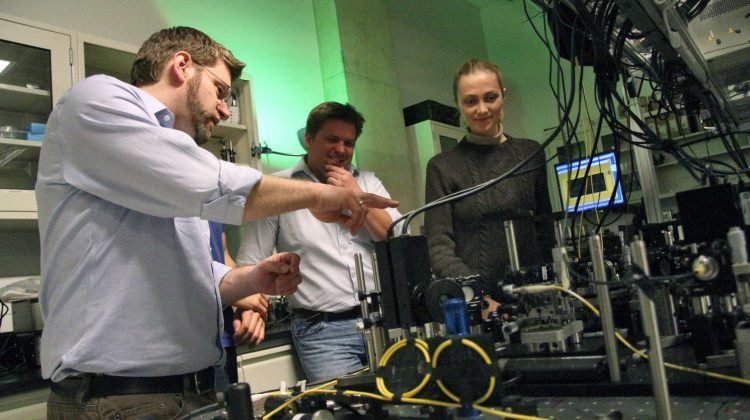

Lang, the computational scientist, has been involved in making sure that the software allows the instrument to gather the images from the parts of the sky that the researchers want to study.

DESI has about 5,000 robotic fiber positioners. So the early work on DESI involved making sure that each of those 5,000 little robots would position the fibre optic cables precisely, so the light from the galaxies the researchers want to observe would come in at the right spots.

In the process, they were building a two-dimensional map of the sky to choose the galaxies from, “so that we could then follow up and get the three-dimensional positions for them,” Lang says.

Percival, meanwhile, is involved in the data analysis. Prior to arriving in Waterloo, he was in the United Kingdom, where he led a grant bid that allowed the United Kingdom to join the DESI project.

But the work began even before that. Starting in the late 1990s, Percival was working with data sets giving the “redshifts” of galaxies moving away from us. That led to the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and the eBOSS experiment that was part of it, used to conduct a major multi-spectral imaging and spectroscopic redshift survey and precisely measure the expansion history of the universe from when it was less than three billion years old.

Those prior surveys gathered a lot of the evidence for dark energy that we currently have.

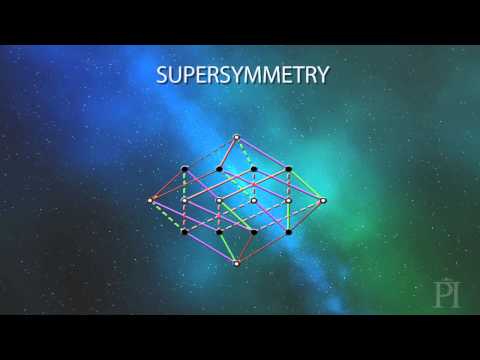

But we still don’t understand this force. Percival says we have a “mathematical framework” that dark energy fits into, based on Einstein’s general relativity, including his cosmological constant, but that doesn’t explain what it is.

DESI will take us deeper. It will allow us to gather information about the distance between galaxies and the distribution of those galaxies, most of the way out to the observable horizon of the early universe.

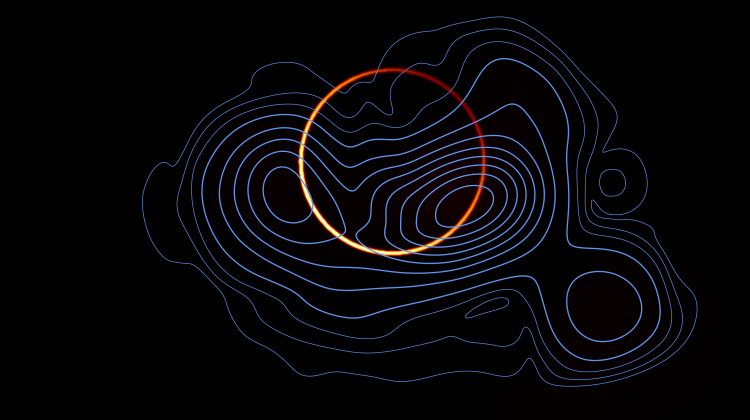

It will allow scientists to gather the data about the patterns of the galaxy clusters, the filaments and sheets of matter we see, as well as the voids in between where there are few galaxies.

Those patterns can be turned into a beautiful 3D map that will tell us about how the universe has grown over the course of different epochs, and scientists can then study that detail to develop better theories about dark energy.

This is part of a long quest to understand the cosmos, one that can be traced all the way back to Albert Einstein’s cosmological constant, a quantity called lambda, over a century ago.

Before that, the universe was thought to be static and unchanging. But Einstein, when trying to apply his theory of general relativity (his theory of gravity) to the universe as a whole, had a problem. It led to a model of the universe that wasn’t stable. The equations showed that if the universe was static at the outset, the gravitational attraction of the matter would make the universe collapse in upon itself.

So Einstein, collaborating with Dutch astronomer Willem de Sitter, added a new fudge factor, a cosmological constant or lambda, to his equations. Lambda implied the existence of a repulsive force that would counteract the gravitational attraction and keep the universe static.

But in 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered that universe wasn’t static – it was actually expanding. Whether Einstein actually called it his “biggest blunder,” as reported by his contemporaries, we don’t really know. But in any case, once he knew that the universe was expanding, Einstein abandoned the idea of the cosmological constant.

Then, in 1998, looking at the data from some of the furthest galaxies in the universe, scientists made the startling discovery that the universe is not just expanding, that expansion is actually speeding up!

Maybe Einstein’s blunder wasn’t such a big blunder after all. His lambda –describing a repulsive force pushing spacetime apart – seems to fit with we now call dark energy, even though we don’t really know what this force is, or why it is there.

With DESI finally sending back data, both from the initial validation stage and the bigger data sets to be revealed in the coming months, anticipation is running high for members of the DESI team.

“We are excited. It’s working incredibly well,” Percival says.