What is it like to be a woman in physics?

Perimeter students, researchers, and staff share their experiences in celebration of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

Take a self-guided tour from quantum to cosmos!

Perimeter students, researchers, and staff share their experiences in celebration of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

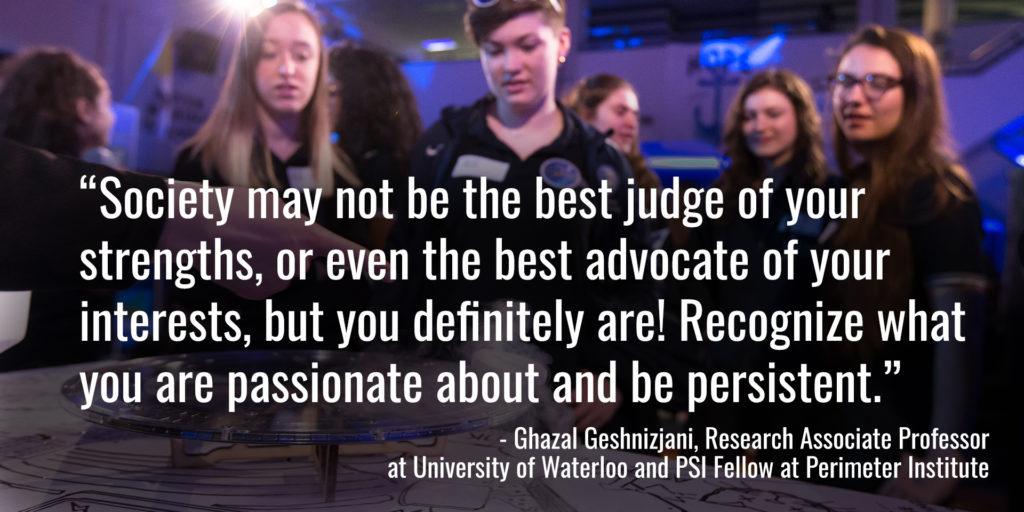

February 11 is the International Day of Women and Girls in Science. In celebration of this day, and as part of the ongoing conversation about the lack of diversity in physics, the Women in Physics group of the Inclusive PI Platform (a grassroots, volunteer-led initiative at Perimeter) asked women-identified researchers to tell their stories.

Here, students, researchers, faculty, and staff share what it is like to be a woman in physics.

Note: Perimeter has been collecting these stories in advance of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science since 2022. The collection below represents submissions obtained over three years, with the most recent ones first.

Embarking on a journey into the cosmos of physics, I found my path paved by the scientific aptitude inculcated by my parents – both science graduates with dreams that I would become the scientist they aspired to be. My mother, a pillar of strength, consistently emphasized that women possess resilience and the capacity to achieve anything they set their minds to.

Coming from a modest town in India, my education was marked by a lack of resources, emphasizing learning but neglecting the art of critical questioning. Excelling academically through school and college, I soon realized that the habit of asking questions was the missing link in my pursuit of knowledge. Even during my PhD, I hesitated to voice the inquiries that lingered in my mind. Motherhood proved to be the catalyst for change. Raising children highlighted the importance of asking questions, an essential skill that I had overlooked. I realized that questions were not signs of ignorance, but gateways to understanding. This newfound perspective transformed my academic journey and lead me toward self-discovery.

Being a woman in the field of physics came with its unique set of challenges, but the unwavering support from my family became my anchor during troubled times. Despite lingering self-doubt, I embraced the universal truth that not everyone knows everything. If I couldn’t find answers, I decided to look for them on my own. This made me really love physics, and my interest keeps growing.

Engaging with students has been both enjoyable and enlightening for me. A significant portion of my knowledge comes not from textbooks, but from the conversations I’ve had with my students. The variety of viewpoints expressed by these young minds has reignited my curiosity for physics, highlighting that curiosity knows no age limits.

As I embark on this journey, my shared theme remains constant: to learn as much as I can. I keep reminding myself that with determination, support, and an insatiable thirst for knowledge, we can break down barriers and leave an indelible mark in science.

I had my first fascination with physics in high school when I read Richard Feynman’s book, Quantum Electrodynamics. I didn’t understand many of the details then, but I was fascinated by the way Feynman presented them and that our world can be described in such a simple, beautiful way. I would read the book for hours in the library, totally absorbed. Ever since, I have wanted to be a great physicist who sheds light on how the universe works and, ultimately, who we are.

My path to pursuing physics, however, did not come very easy for me, at least in my own perception. I grew up in South Korea, where gender roles have a clear division and women are markedly underrepresented in physics and mathematics. I grew up hearing so frequently remarks like “Smart women cannot get married,” “STEM is masculine,” and “Boys are naturally better at STEM.”

Even after I came to the United States, the situation was not so very different – although I didn’t hear such direct comments, I was one of only three female students in my physics class, and during competitions, I often felt discouraged because boys formed teams exclusively among themselves and assigned easier problems to girls’ teams. This experience put a glass wall in my mind between me and my love for physics. Before every physics problem, I couldn’t help asking myself, “Am I too slow? Can I do this? Can I really do physics?” I knew, and I strived to believe, that I could, but having this self-doubt distracted me from solely focusing on learning what I love and enjoying the process.

Nevertheless, I gradually recovered from this wound as I attended higher education and began research. First of all, discovering new captivating topics in physics left little space in my mind for doubt. I worked hard to gain as much understanding as I could, and the joy of finally grasping something made me feel nothing else mattered: What else could be more fulfilling and happier than learning physics? No one could stop me from feeling this joy!

Also, doing research taught me that there is no single definition of a great physicist. I had always thought that “great physicists” are those who are fast at figuring things out from a young age. Yet the actual doing of physics had so much more colour to it – it involved a lot of creativity, discussion, collaboration, and genuine human connection. I finally convinced myself that I don’t need to fit myself to the physics community, which I thought was too narrow. Physics was already, and always had been, open to me, and I just needed to enter and thrive.

My advice for women and girls in physics (myself included) or anyone aspiring to do physics is to focus on oneself and never give up. No matter what your culture or other people say, just gaze on what you love (or an ambitious goal!) and work hard, and then your worries and uncertainties will dissolve. Also, it helped me greatly when I spent less time comparing myself to others. Since we all learn at different paces and in different ways, we should rather celebrate our uniqueness and enjoy the diversity of people and ideas.

Lastly, find a physics community you love that supports you, like I have with Perimeter. I cannot thank enough my PSI mentor Giuseppe Sellaroli, my fellow PSIons, and the teachers and staff at Perimeter for inspiring and empowering me, and teaching me how happy just learning and being immersed in physics can be. The path to physics may have a barrier, but I am sure we can find a way to break it or pave a new path.

Growing up, I was always a curious child and had a broad interest in both social and natural sciences. However, pursuing a career in physics never crossed my mind until I was already in my mid-20s. It took me so long mainly because of the internalized belief I had since primary school that I wasn’t quite cut out for physics.

In my hometown in China, coaches for science Olympiads would regularly select kids from schools for special training. I was never one of them. It was often considered that those picked for Olympiads could have careers in math or physics while the rest were probably not smart enough. This idea was even stronger for girls. For boys not selected, people would say it might be just because they were young, a bit mischievous, or not focused enough. But girls, even with good grades, were sometimes brushed off with claims that boys would outshine us in math and physics eventually. These societal attitudes led me to believe that physics wasn’t for me. Thus, when it came time to pick a university major, I chose finance, a field considered suitable and promising for me (and I was also interested in it, among many other subjects).

While I enjoyed learning about finance, I didn’t feel a strong passion for its career path. This led me to a gap year, volunteering as a teacher at a middle school in a rural, underprivileged area of China. Faced with a teacher shortage, despite my finance background, the school assigned me to teach science. This school, like many in China, categorized students into ‘advanced’ and ‘normal’ groups; mine were the latter. My students, although naturally curious about the world around them, had little academic self-confidence because they were in the ‘normal’ group, much like how I had viewed myself as unsuitable for physics. In trying to get them interested in science and to believe in themselves, I ended up reigniting my own passion for science and, gradually, found myself increasingly drawn toward physics.

But even then, I didn’t consider switching my career to physics; my plan at that time was first to establish myself in finance, earn enough money, and then study physics as a hobby. After all, one doesn’t need to be exceptionally smart to be a hobbyist. As such, I proceeded to do a master’s degree in finance.

A year into the master’s, an unexpected opportunity to study in New Zealand came up. Still, I didn’t immediately choose physics. It took two more years of undergraduate studies in various STEM subjects before I finally committed to physics. It was largely because New Zealand had a more laid-back education system than China and my physics teachers and classmates were extremely supportive. There, my hard work was recognized, which boosted my confidence. This experience, together with my childhood experience and what I saw during the teaching year, really showed how much your environment can influence what you think you can do and achieve.

I was later accepted into the PSI program at Perimeter, but soon faced imposter syndrome since many of the other PSIons could think much faster and were more academically prepared than me. I worried that maybe I had somehow deceived the selection committee into accepting me. Even now, as a PhD student at Perimeter, I still have similar doubts now and then. But I keep telling myself that, until I’m discovered to be a fraud or only here out of pure luck, I should just try to learn as much as I can and cherish this opportunity, especially since there are people around me who sincerely support me to be here.

As a final note, for girls who are concerned about the gender ratio in physics: my finance classes had more women, but in my experience, awareness of the value of gender parity is higher in physics and the solidarity among women in physics is inspiring. My path in physics has received tremendous support from peers, teachers, mentors, and others. There are still many inconveniences and barriers for women in physics, but please don’t let them hold you back or listen to the ones trying to discourage you. Just by being a woman in physics, you will already be making a difference and we will share your journey, celebrate your achievements, and stand with you in the challenges.

When I was little, I wanted to be a writer. As I grew up, I started veering towards maths and physics, and it disappointed my inner child a little because it just didn’t feel like I was going to end up with a very creative job. I ended up choosing astrophysics as my career without a very strong reason, but my passion grew as I learned more about it. Slowly, I started to realize that being a researcher was, in fact, a job that required plenty of creativity!

I did most of my career in Argentina, which has one of the highest percentage of female researchers in astronomy across the world. This was very encouraging, but even in such a welcoming environment, I still crossed paths with some people who thought it was pointless for women to go into academia. I was lucky to have such a good roster of good role models around me that proved these men wrong and gave me hope that this path could work for me no matter what choices I made regarding my personal life going forward.

Science is still as magical to me as it was when I was 10, and I am grateful that I get to do research for a living, since I’ve found it very rewarding and way more entertaining than I would’ve expected a job to be. It is always challenging, but the key is in surrounding yourself with people who will support and value your work, and who you trust to go to for advice when needed. I hope to be a good mentor to the next generations, and to make physics a more approachable field for anyone that feels it is not for them despite their passion for it.

I am always very excited to hear about why someone fell in love with physics. That shared passion binds me with many different people with very diverse life experiences.

When I was young, my mother gave me the book George’s Secret Key to the Universe. I was captivated by the pictures of the Milky Way and the fantastical stories about trips through wormholes. At the time, I didn’t even know who one of the authors, Stephen Hawking, was, but the stories were so amazing that I kept reading. Similarly, I will always remember the books La puerta de los tres cerrojos and The Elegant Universe, where I learned about quantum physics and string theory. Now, I am a master’s student in the Perimeter Scholars International program, where I am trying to learn as much as possible. While my interests have since drifted from astrophysics and cosmology, I am still driven to understand how the universe works. I am now studying quantum field theory, holography, quantum gravity, and other topics in theoretical and mathematical physics, and these are the areas I am pursuing for my PhD.

My undergraduate studies were in both physics and math. In university, some of my professors were very generous, as they were always happy to spend hours telling us about advanced topics. Something that changed my life was hearing the phrase “SU(2) is the double cover of SO(3)” in my first year, followed by an explanation I did not understand. I have spent many years trying to understand and discovering many exciting facts from that sentence. I also made many friends in physics and maths with whom I worked collaboratively, and this style of learning has deeply affected me. At Perimeter, I have had the pleasure of meeting students from across the world who approach problems in unique ways, and this has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. We are encouraged to work together on assignments and interviews, and to share as much exciting physics as possible. Occasionally, we organize small talks to present to each other, and I am always amazed by how others think and explain what they learn. PSI’s collaborative environment makes it easier for everyone to share their ideas without feeling judged and helps everyone feel valued.

Diversity and collaboration are two things the scientific community lacks, and both are related to the poor experiences women have in physics. In my first year of university, I realized that I had internalized some bias: while reading about the Peccei-Quinn mechanism, I unconsciously assumed that Quinn was a man. At first, I was angry with myself; however, now I understand that this was not my fault. There are collectives that have been excluded from artistic, scientific, and social development throughout history, and, because of this, humanity as a whole has suffered greatly. The representation of historically oppressed groups is crucial in encouraging the next generation of scientists, but representation alone is not enough. We need to recognize neglected contributions by women in science and acknowledge all the women who have quit due to the hostile environment. All academics have a shared responsibility to combat and end the discrimination of marginalized groups, by implementing policies that make everyone feel as though they belong in the scientific community. The future of science depends on this change, and we should all be active participants.

Research is an essential part of society, and it is imperative that in the research community everyone feels included and is able to reach their full potential. Physics also is not isolated from the rest of academia, and we need to explore its relationships with other disciplines. I love poetry, and I am inspired by the poets who have joined it with physics. Learning about María García Diaz’s poetry was life-changing for me, and there are countless other examples of inspiring interdisciplinary scholars.

The most difficult thing for me has always been thinking that I am not good enough to do theoretical physics – the feeling that even if I try very hard I will not be able to contribute to novel research. I know that this is a common feeling in students, especially among women, and it prevents many girls from working in science. I always try to tell myself: you have your own perspective to show the world and that is very valuable. Everyone should pursue the topics they are most passionate about, and I would tell a younger version of myself: focus on how much you love what you are learning.

Until my last semester as an undergrad at ETH Zurich, the topic of feminism and “women in science” was not something I thought much about. During those last few months, a friend of mine launched a book club. One book in particular stuck with me: “x + y: A Mathematician’s Manifesto for Rethinking Gender” by Eugenia Cheng. I liked the way it shifted gender discussions: We don’t necessarily need to group behaviors into characteristically feminine and masculine. Instead, we can focus on a goal we can agree on: Moving towards a research environment that is as collaborative as possible. Of course, it can be fun to compete with each other at times. But, at the end of the day, we are humans and feel strong when we are valued by the humans around us. Share with each other, listen to each other, learn from each other.

Being a woman in science never felt special to me: I always felt just like a regular part of the community. I grew up in Croatia where this was not a big deal. I went to a mathematically oriented high school, where girls were among the best students, and about half of the students in the class were girls. Later, at university, while doing a physics degree, we were still always well represented. Sometimes people from other countries would be surprised to meet us, a group of girls who wanted to do math. In their countries it was unusual, and thought of as more of a guys’ thing. We found this curious and funny. I didn’t think much of it.

Now, to be fair, I think that at some point in a physics career, a serious problem can arise. Somehow it seems that women tend to leave physics once they finish their PhDs. To me, it seems quite probable that this is due to the clash between the demands of building a career in physics and the time pressure of settling down. This affects both men and women, but women are more severely impacted by it. It’s hard to create a family when you’re moving every couple of years, first for a PhD, then postdocs, and then hopefully you settle down in late 30s or early 40s.

When it comes to me and my path – I love physics and research, so I will keep doing it for as long as I can. I can see that at some point the demands of following my heart on this front might come in serious conflict with my desire to start a family. I guess I’ll figure it out.

Hopefully one day we’ll be clever enough to set up a system that doesn’t require young scientists to move around so much, and often sacrifice the parts of them that are very human: the desire for family, friends, stability and intimacy. If we argue for this as human beings, we see quickly that’s the right thing to do. Even viewed pragmatically, it is not clear that the sacrifices scientists make are contributing to the development of science itself. They might be making everything worse.

After all, there are many examples of people who have made important contributions without needing to uproot their lives. The famous philosopher Immanuel Kant, for example, never in his lifetime left his hometown – yet his great work in philosophy is known worldwide, centuries after his passing.

At the end of high school, when I had to choose what to study at university, I was torn between history and physics. Weird, you might think. However, both subjects have something in common: they help us understand why the world is the way it is.

Because I loved mathematics, I chose to study physics – although at the time I knew very little about it. For instance, I had never heard of quantum mechanics until I attended the relevant class at university.

At university, I found an environment full of passionate and (mostly) kind people. I have never regretted my choice and I am thrilled to be pursuing my career as a physicist.

The main barrier I encountered is the impostor syndrome. It is indeed easy to feel insecure when facing the challenges in physics, and its complexity. For example, you often start reading a paper without understanding much of it. Talking with my peers, I realised that most of us feel the same way and that it is perseverance that matters.

Understanding the universe is still what drives me everyday and I’m very fortunate to do it by working as a postdoctoral researcher at Perimeter Institute.

I got interested in physics by reading some pop science books towards the end of high school. Curiosity about what the universe is like and how it works initially drew me in, but what really hooked me was the realization that the science I was reading about wasn’t just information that existed abstractly “out there.” Rather, it was knowledge built over time by people working, deriving, experimenting, and more generally figuring things out.

It still took a couple more years to understand that there might be career options where I could actively contribute to that “figuring-out” process myself. I feel lucky to have the opportunity to do that now, working on cosmology research at the intersection of theory and data analysis. With collaborators from all over the world, I use measurements of distant galaxies to map the distribution of matter in the universe, and use that to study the properties of dark matter, gravity, and dark energy.

An important piece of my growth both as a person and as a scientist has been recognizing ways that intersecting inequities in society – including, but not limited to, those related to gender – impact the human aspects of doing science. The lack of representation of women in physics is one manifestation of this, and was an initial prompt for what is definitely still an ongoing learning process for me. Things that I’ve found valuable for this learning process include having good supportive mentors, proactively looking for ways to help others – especially more junior scientists – feel welcome, and building community with people working together to make more structural improvements to our institutions.

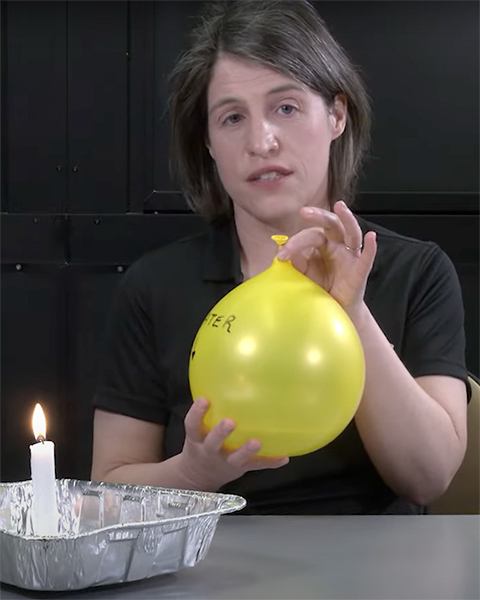

Unlike many of my colleagues, I haven’t always known that I wanted to be a physicist. However, I’ve loved teaching for as long as I can remember. Throughout my childhood, one of my favourite activities was playing “school,” where I would set-up a classroom and try to convince my younger brother to be my student.

Now, many years later, I still love teaching – but now rather than teaching arts and crafts to my reluctant brother, I teach quantum matter and computational physics to graduate students. I’ve also discovered a love for scientific outreach and communication, which I think of as another form of teaching. It challenges me to explain the goals and methods of modern physics research to more general audiences and to remove as many technical details as I can from my explanations.

Even though I am excited about the work that I do, there are some days when I lose my sense of belonging or feel discouraged because I notice that I am surrounded by other researchers who have felt an unwavering commitment to physics since the first moment they turned on a light switch or looked up at the night sky. But in those moments, I remind myself that one of the keys to progress and breakthroughs is collaboration. The best scientific work is done when we incorporate people with many different passions and perspectives. My passion for teaching has led me to play a unique role in communicating today’s theoretical physics to others and in growing the community of tomorrow’s scientists.

As a child, I was fascinated by math and logic. When I was ten, I started watching documentaries on famous theoretical physicists and reading various books by Stephen Hawking and Roger Penrose. That was enough to trigger my interest in the physics of our universe, and to decide that I would ultimately like to embark on an academic carrier and spend my days at a blackboard. This idea motivated (and still motivates) me to work hard towards achieving my goals, even when failures outweigh successes. Currently, I am a postdoctoral researcher at Perimeter Institute, where I work on quantum gravity and its phenomenological implications in astrophysics and cosmology.

I grew up in Bucharest, Romania. I only started liking physics in high school, thanks to an inspiring teacher. Suddenly, physics turned into an interesting subject which used math to explain facts of everyday life: why glasses help if you have blurry vision, how engines and radios work, or how temperature can be measured. In all my classes girls were the majority and my physics teacher was a woman so I wasn’t really aware of the gender imbalance in the sciences until much later.

I think that what we become is in part determined by our surroundings and experiences. I was extremely lucky to continue being surrounded by remarkable people, including mentors, colleagues, and friends, throughout undergrad and grad school. This allowed me to focus on doing what I liked best and at every step I was encouraged to do so, which is why I’m still in physics today.

For as long as I can remember, I just loved understanding everything around me. As a kid, one of my favourite books was The Usborne Children’s Encyclopedia. I would read it over and over, front to back, until there was nothing inside that I didn’t know – and then I would read it some more.

Maths was a game to me. I couldn’t get enough, and I would often work ahead of the rest of my class, just for fun. (I know that sounds so nerdy!) I was also doing the usual kid stuff – climbing trees, hide and seek, playing football and camogie – but I just really loved my books. My childhood best friend recalls me arriving to our slumber parties and never understanding how, when she asked me to “bring something fun,” I would arrive with my latest favourite book. As I got older, I realized that physics combined all of this – knowledge, maths, even the mechanics of sports – and the more you learn, the more you want to learn.

Allies were key to overcoming any barriers. It was so valuable to meet people who took an interest in me for all the right reasons, who pushed me to succeed and supported me; I know they want me to succeed as much as I do, and they will always have my back. That can mean a lot, especially when it comes from those in more senior positions. Knowledge is also handy: when someone underestimates you, there’s nothing more satisfying than blowing them out of the water with pure knowledge.

There’s always so much more to learn and understand, and I just love that. Add the applicability of methods in mathematics and physics to all different areas of research, it’s kind of mind-blowing what we are all capable of … if you just put the time and patience towards it.

There will be always people eager to set your future, but you’re the one that has to live your life! Follow what intrigues you, the questions that keep pulling at you. When I decided to study physics, many people told me I wouldn’t get a job in doing physics. Later I was told I shouldn’t specialize in quantum gravity. But I found a path. What pulled me along every step was being passionate in what I was doing.

As a kid, I liked checking out library books that featured patterns, puzzles, numbers, and optical illusions (Anno’s Alphabet and Anno’s Counting Book are some fun examples). I liked thinking about numbers. Apparently, I once asked my mom when I was quite young, “What are four threes?” When she said, “Twelve,” I looked up and said, “You’re right!” with a great deal of joy.

I enjoyed science somewhat, but mainly because the experiments and demos seemed like cool magic tricks. I wasn’t interested in memorizing a lot of facts, and that’s mainly what science seemed to involve before high school. Learning chemistry was a game-changer, because it made me realize that all the fun math games that I played could be used to understand nature.

Later, physics showed me that nature could be understood from the ground up using mathematics. I remember learning about the different orbital shapes in an atom, but my textbook told me it would take several years of college math to actually understand them. The idea that I could use math to derive such things felt surreal and exciting. I decided then that understanding how this worked would be my long-term goal. This led me over the years to condensed matter physics.

I owe a lot of my path to the encouragement of my mom. The rather traditional and conservative community in the US where I grew up was not supportive of women having careers. Despite this, my mom (who educated me) always encouraged my interests and exploration, and I knew that she thought I could do anything that I put my mind to. Beyond that, it’s the fun of the puzzle, supportive colleagues, and great friends I’ve met along the way that helped me chart my trajectory.

I had a very indirect journey into physics. At different stages growing up, I wanted to be (in no particular order): a children’s author, a doctor, a playwright, a diamond hunter, and a film director! I first got into physics in my teens when I happened to pick up a book about the universe and I was amazed by how many things have yet to be discovered. To me, physics seemed like puzzle-solving on a bigger scale.

One of the things that helped the most during my undergraduate degree in physics was that my classmates and I realised that encouragement rather than competition would help us all. We never had to pretend that we understood everything all the time!

Some of my biggest barriers to physics were my own preconceptions. I thought physicists would all be like the main characters of The Big Bang Theory – science ‘geniuses’ who had little interest in the ‘arts’ side of things. I couldn’t have been more wrong: the people I’ve met in physics have very diverse interests and personalities, and most would agree that it’s hard work and enthusiasm rather than ‘genius’ that helps one to succeed.

My father is a researcher in molecular biology. When I was a child, I sometimes went with him to his laboratory rather than stay at home alone. It was a very beautiful game: I could see cells in the microscope, the extraction of DNA, and ask a lot of questions of his postdocs. Being kept away from the dangerous centrifuge made everything more mysterious.

At home, I had a toy microscope and a chemistry kit for children, and I would play with it when I was not at school. My curiosity was fed by the feeling that learning about science was natural, and it never crossed my mind that science was not for women. This enthusiasm in understanding more of the world we live in still drives me today.

I was born in the ancient city of Esfahan in Iran at the eve of a very violent revolution. Revolution was soon followed by the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq. During that tumultuous era, I went to an overcrowded primary public school, like all the students in my generation. I was an introverted child. Teachers would hardly notice me in the class, except for a couple of math contests in which I had “magically” outperformed all the stellar students.

My last year of primary school coincided with the last year of the war when, due to the intense ballistic missile attacks, schools were closed for most of the academic year. That same summer, a special school program for gifted students opened two branches (one for girls and one for boys) in our city. To the surprise of my teachers, I ranked very high in the entrance test and was accepted to the female branch of the enrichment program.

Once again, I was not a stellar student among my new peers, many of whom are now doctors and engineers back home and around the globe. However, gradually I recognized my strength was in analytical thinking. What I enjoyed the most was solving problems in math or science classes. Over time, my interest turned to theoretical physics: the place where math and nature meet each other.

Fortunately, I found a small group of friends in high school who were just as passionate about math, computer science, and physics as I was. We formed study groups, shared interesting books, and organised workshops. We also learned very early on that not everyone, even in the educational system, believes that girls should pursue math or science. Thankfully, we were determined to help each other face any obstacles.

For example, when we learned that some resources such as computers and telescopes had been shipped to the boys’ branch of our school. We talked to the director and convinced him the resources should also be shared with the girls. Another time we learned an extracurricular physics course had been arranged for boys. We organised a group, went directly to the boys’ school (during school hours), and refused to leave until they let us participate in the program. Just imagine: a half dozen girls having a sit-in at an all-boy high school, eventually convincing the principals of both schools that it was our right to participate.

My journey, from those days as a young girl determined to learn science in Iran to later studying and working as a Middle Eastern female physicist in North America, has been long and not at all straightforward. I was very lucky in many aspects: I got into good schools, had a supportive family, and stumbled upon very good friends and scientists who helped me face many challenges. But I have also been very persistent in finding ways to overcome barriers.

If I could offer some advice for our younger generations, one is that society may not be the best judge of your strengths, or even the best advocate of your interests, but you definitely are! Recognize what you are passionate about and be persistent. Second, try to find a good support network of people like you. It will not only help you face challenges along the way, but also you will make many enjoyable memories together.

I knew physics was for me the day we learned about torque in high school. I spent the rest of the day smiling each time I opened a door. It was so cool to understand how things worked! It was this joy that pushed me to keep pursuing physics. There were certainly days where I was the only girl in the room, but I always felt at home with my physics friends, because we shared the joy of trying to understand the universe.

I decided to study theoretical physics, and later specialize in general relativity, when I discovered how much it related to mathematics. I keep being very enthusiastic about my work and all the people I had the chance to meet. Although the further I went in academia, the fewer women there were, I never faced major problems in the countries I have worked in. The only effect it has had is to progressively make me more and more engaged about encouraging women to do science.

I always had a lot of fun with math, since elementary school. I still remember the day on which I ended up in a higher-grade class and learned about Pythagoras’s theorem, at a younger age than most. I could not stop bragging about it and asking my mom (who had a degree in statistics) for more details, like showing me the beautiful geometrical representation of the theorem.

At the same time, I was always passionate about stories and writing. When the time came to pick a university degree, physics seemed like a good compromise: by studying physics, I could have fun with math, put my brain to good use, never be bored, and learn the amazing story of how the universe really works.

Now, after four years of graduate school, some of what drives me to continue my work and pursue this career are the amazing people I have met along the way. Science, after all, is a collaborative effort, and working in a team (most of the time, of your own choosing!) is one of the greatest pleasures of a research career.

I always loved maths and had fun with them. I particularly remember a female teacher I had when I was in middle school who taught me about geometry and what the meaning of doing a proof was. I loved it. As a high school student, I wanted to be an oceanographer. But when I discovered physics after starting university, I changed my mind! Because of my love for maths, it felt natural to go into theoretical physics.

The always-exciting journey into physics also introduced me to some really amazing people. Some of these awesome people provided a great deal of support, which compensated for the very minimal support I received from academia when I had my first daughter as a postdoc. Now, most of these people are much more than colleagues – they are true friends.

Have fun learning science and look for the passionate people on your way!

My name is Marina and I’m from São Paulo, Brazil. I’m 21 years old, and currently I’m a Perimeter Scholars International master’s student.

I wanted to be a scientist since I was a kid, and my parents encouraged me a lot. I was also very inspired by scientist characters from cartoons! Looking back, I think all those scientist characters were male, which is sad. I’m sure I would have been very happy to see a woman represented there when I was little!

This lack of contact with women in science persisted for most of my journey, and it was one of the main barriers I encountered. In middle school and high school, I participated in Physics Olympiads. Many times, I was the only girl in the training group. The worst part was the sensation that if I did well, people would think it was because I’m a good student, but if I didn’t perform as well, it was because I’m a woman. At the time, this put a lot of pressure on me.

Overcoming these negative feelings is still an everyday fight, but I think that what helped me the most was getting in contact with more and more girls and women in physics along the way, being able to talk about it, and listening to other people that had similar experiences.

I recently finished my undergrad and I’m now doing my Master’s research in the foundations of quantum theory, a theory that was developed in the last century and that talks about the behaviour of very small things, such as subatomic particles. What drives me to pursue physics, and this topic in particular, is the same curiosity that I had back when I was a kid: figuring out how reality works on a fundamental level.

I recall saying that I really liked physics, and my parents told me to do what I liked, so I just went for a physics degree. Now I am doing a PhD and honestly, I have no regrets. I don’t think any other kind of job would have been so rewarding (yet so frustrating at the same time). What about barriers? I’m very lucky to not really have encountered any so far – but maybe it is because I am oblivious to them. Either way, with all the recent awareness and positive affirmation regarding women in physics, I really believe it is a great time to pursue physics if that’s what keeps you awake at night.

I was still a child when I discovered my flair for maths. As a middle schooler in Gaya, India, one of my hobbies was solving general maths and reasoning problems in a monthly magazine aimed at those taking general competitive exams after graduation. In high school, I was captivated by optics. It was very intriguing to understand how concave mirrors and convex lenses form real images just by considering a few rays of light.

I reached a turning point when I learned about Newtonian mechanics. It was mesmerizing: that simple equation, F=ma, (commonly known as Newton’s second law) was packed with so much power. In addition to explaining the motion of mechanical objects, it can even explain the electrodynamics at play in the surroundings. Comprehending the significance of such seemingly simple equations inspired me to pursue physics research.

Although not easy, the journey from high school to postdoctoral research has been enriching. In a society where engineering and medicine were considered the most respected career paths, choosing a science career came with its own set of challenges. I settled at the crossroads of science and engineering by enrolling in an “engineering physics” degree at a prestigious engineering institute. However, I soon started to feel out of place. I decided to take a risk and join a newly established science institute where no one had graduated yet. Despite some warnings from others, I followed my instincts.

I quickly felt at home in the new institute, surrounded by students who shared my passion for physics. It was not normal for a small-town girl from a conservative society like me to leave home for undergraduate studies, let alone later travel to a foreign country for graduate studies. I faced a lot of conflicts within my family; nonetheless, I remained undeterred. Despite these conflicts, they have ultimately been supportive. They have grown happier over time witnessing my past risky decisions coming to fruition.

During my undergraduate studies, there were moments when advanced, fast-paced coursework felt overwhelming. Summer research projects provided a refreshing break from coursework. I was able to pursue physics problems freely, working with professors across the country, which was genuinely satisfying and illuminating.

Fast forward to graduate studies: it was enriching to spend most of my time “doing physics” rather than only learn the existing concepts. I had my share of low moments during graduate studies though. Before my first committee meeting, I felt that I had not done enough and thought maybe I should quit. Realizing that it was just my fear of vulnerability helped me to stay grounded. Making sure that I did not lose my momentum in research by continuing to do at least a bit of physics even during these low phases was my key to successfully completing graduate studies.

I grew up in a patriarchal society with strict gender norms. Witnessing women’s hardships in these surroundings led me to a conviction that I want a better life. I want to live life on my own terms. This conviction has served as an anchor, motivating me to give my best to whatever I am pursuing. I truly wish that all girls and women can recognize and pursue their dreams even when it means breaking the gender norms and stereotypes prevalent in society.

In high school, I remember spending days trying to come up with a perpetual motion machine – something I was told was forbidden by nature thanks to the second law of thermodynamics. Perplexed, I continued to design variations, all of which fell short of being, well, perpetual. Instead, my fascination with nature’s inner workings became perpetual.

Back in India, I was around many girls in school, but as I prepared for college, fewer stuck with physics. By the time of my undergraduate degree, I was the only girl in the batch of around 30 students. It felt like a superposition of being isolated while also being under a spotlight. This was when I often presented as a tomboy to fit in; it was only later that I slowly became comfortable with the concept of presenting femininely while simultaneously pursuing physics.

Perhaps it is easy to claim that physics is beyond gender, but our experiences are not. It has been the support through community – be it parents nurturing my dreams, schoolteachers appreciating my ideas and mentoring me, or amazing contemporary female researchers paving the way forward – that has kept me striving even as statistics deter. That and the endless puzzles hiding in nature, waiting to be solved. For the budding womxn physicists, I want to affirm and assert: your voice, your ideas, and your presence matters. We are here and we are rooting for you!

I am a female mathematical physicist/mathematician. Since my childhood, I deeply loved nature, and greatly enjoy activities like observing plants, hiking and camping. As a teenager in Singapore, I read many good popular physics and math books in public libraries and was amazed by many interesting physical phenomena that are not visible in daily life. At that point, I decided to start an intellectual journey related to physics.

During my journey, apart from my personal efforts, I find it very valuable to help others, as well as seek help from kind mentors, peers, colleagues and collaborators, etc. As a college student in Toronto, Canada, I benefited a lot from the kind advice of many mathematics and physics professors, and they influenced me to pursue graduate studies in mathematics/mathematical physics. Similarly, my research works at University of California Berkeley (as a graduate student) and Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (as a postdoctoral researcher) would not have been possible without the numerous discussions with a large number of researchers at my home institutions and around the world.

Physics, as well as math and science in general, are foundational subjects. Studying them stimulates your mind and opens doors to a wide range of opportunities, including scientific research, tech, finance, business and even politics (famous female politician Angela Merkel is a former physicist).

If you find yourself pondering the secrets of nature, consider following your curiosity and trying out a physics/math/science class, and see where that experience may take you.

Growing up, I had a broad range of interests: science was definitely among them, but so too were reading, writing, art, and theatre. In high school, I had my first deep immersion into theoretical physics – and it was thanks to Perimeter Institute. I attended the first “International Summer School for Young Physicists” (ISSYP), though back then it was known as “Young Physicists of Canada.” When I learned just how much there was still to learn and understand about the universe, I was hooked.

I went on to study astronomy and astrophysics and earned my PhD from the University of Toronto. I was fortunate to meet so many supportive peers along the way. We learned that science was best done as a team, drawing on the strengths of multiple people. Together, we could almost always fill in the gaps of knowledge that any of us had as individuals.

Now, as a science writer at Perimeter, I enjoy telling the stories behind the science – from the hard work that goes into every breakthrough or new discovery to the human side of the relentlessly curious scientists who make them. There are many people who have historically been left out of the stories, and still more who have not yet been able to write their own chapters. Physics will be a much richer place when everyone feels empowered to participate.

Just before I started my physics studies, I was sure that I would not even make it through the first year. I was completely convinced that I was not good enough, although my school grades actually said otherwise. After the first two years, it turned out that I was the best student of my semester and I even got an honour and a scholarship from the physics department of my university.

Simons Emmy Noether Fellow Malena Tejeda-Yeomans is studying heavy ion collisions that recreate the first moments after the big bang.

A round-up of what’s up: the latest news from Perimeter, a look at the recent work of researchers and alumni, gems from the archive, and fun physics for everyone.

“Inspiring Future Women in Science” webinar featuring successful women in science and technology draws participants from around the world