Neil’s Notes: Goodbye, dear Stephen

Cosmologist Neil Turok reflects on the life, work, and unquenchable curiosity of his friend and colleague, Stephen Hawking.

I was an undergraduate physicist in Cambridge when I was fortunate to attend Stephen Hawking’s inaugural lecture as the Lucasian Chair, the position Isaac Newton once held. The lecture was provocatively titled: “Is the end of theoretical physics in sight?” Through a series of light-hearted vignettes, Stephen explained some of physics’ greatest advances. He kept the audience on tenterhooks to the end, as we awaited his oracular answer to the question. When it came, it was as surprising as it was unambiguous. Yes, he said, the newly constructed theory of supergravity, developed by other theorists, was the answer. All that remained was to work out a few details. I left the lecture wondering if physics was really over and whether I should switch to another field.

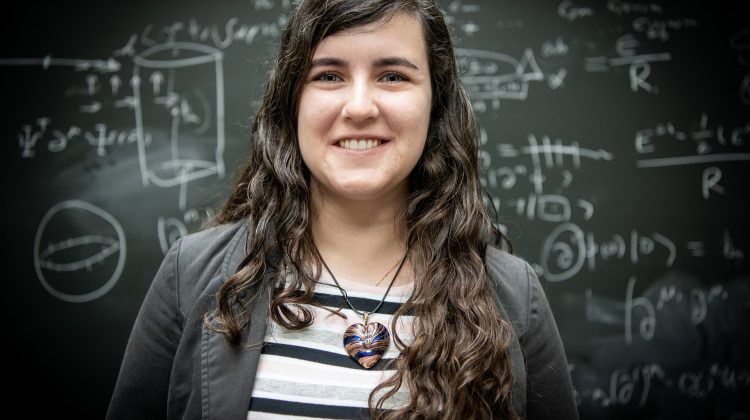

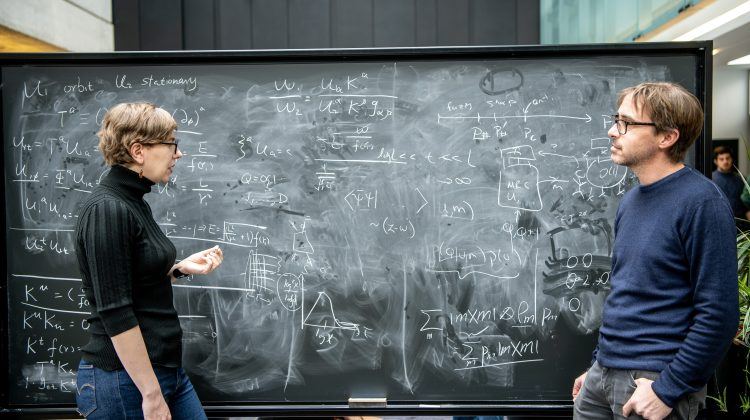

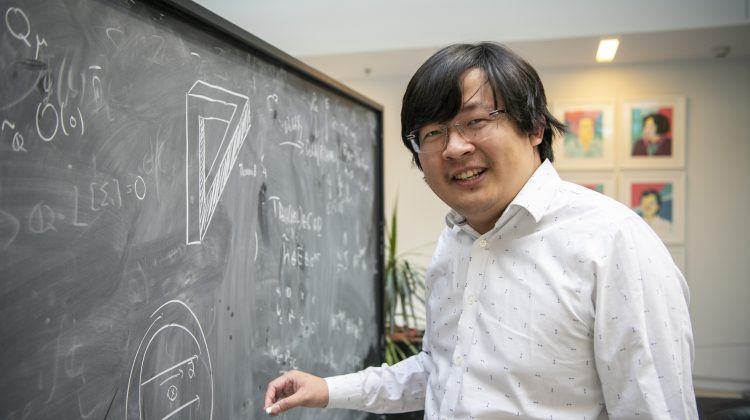

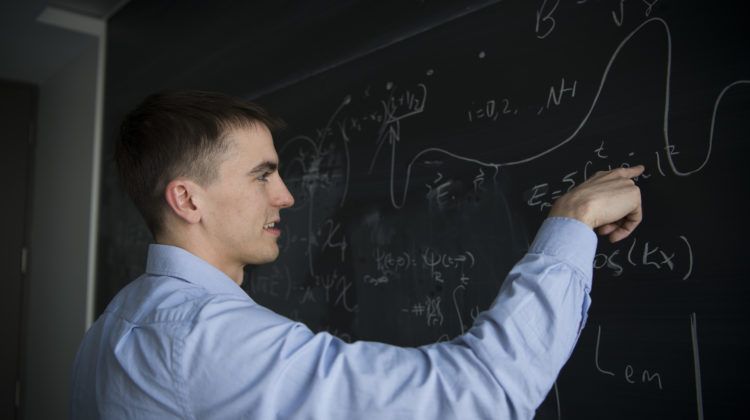

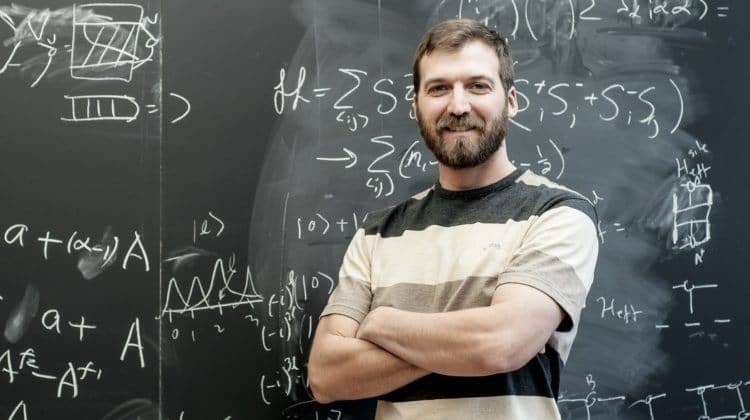

Eighteen years later, I joined Stephen as a Professor at Cambridge. Supergravity had not worked out as the ultimate theory (but interest in it continues to this day). I knew something of Stephen’s elegant and influential work combining quantum theory with gravity in the context of black holes and cosmology, and I was keen to interact with him and, if possible, to learn from him. So I presented a seminar on a topic I hoped might pique his interest – the birth of an inflationary universe. I showed how quantum effects in inflation, like a cosmic magician, allowed you to conjure an infinite universe out of a finite one. To my delight, after the lecture, Stephen said he found the ideas interesting and he wanted to discuss more. Thus began our work together, spending many wonderful afternoons scribbling on the blackboard and teasing out the technicalities. Even more wonderful, we became close friends.

There is so much to say about him, it’s hard to know where to begin. It goes without saying that he was a brilliant scientist of the very first rank. The concepts he formulated and the questions he started to address, many decades ago, are so deep and farsighted that they continue to inspire the whole field. How can space and time be quantum? What happens inside black holes? What principles govern the universe? I feel today we are approaching the answers, guided in large part by observations that were largely lacking when Stephen pioneered the field. Even if the details of some of Stephen’s favourite theories – like inflation and supergravity – don’t survive, I believe that his basic intuition – that quantum mechanics will connect beautifully with gravity,

and the combination will answer deep questions – will turn out to be right.

Despite Stephen’s stature, he never became stuck in his ideas. He was open to questioning everything, to rigorous argument, and to finding new connections. It made working with him enormous fun; it was as if all the physical constraints on his body were mirrored by a total freedom and power of thought. You always got the sense, when discussing science with him, that in the next 30 seconds, we might change everything.

He loved speed and risks and jokes. And bets! In 1975, he bet Kip Thorne that black holes did not exist – a bet he lost. He bet John Preskill that black holes destroyed information. He declared himself wrong in 2002, and gave John an encyclopedia on baseball but encouraged him to burn it, saying that would be as useful as the information which survived an evaporating black hole. He bet me that cosmic inflation would be confirmed by future measurements – unfortunately, we never did settle that one.

Stephen loved the idea of Perimeter Institute. It was younger and much more of a gamble when I was approached to become its second Director. Taking

the position would mean leaving Cambridge and Stephen behind, so I went rather gingerly to his office to tell him and ask for his advice. But when I described Perimeter’s mission – to unify quantum theory and spacetime – his eyes literally shone. Although he said he would be sorry to see me go, I could tell he shared my excitement and would lend his fullest support. Which he did, time and time again.

First, he lent his name to our new building, the Stephen Hawking Centre. And then he visited, twice, despite the massive effort and risk involved, because he wanted to see for himself what this “grand experiment,” as he called it, was like. He loved being here, having scientific discussions in the Bistro, and inviting many of us over to barbecues at his house. He met with everyone – the PSI students, the scientists, and countless visitors who wanted to be introduced to him.

In many ways, Perimeter epitomizes Stephen’s aspirations and his vision. He believed, as I do, that the astonishing simplicity and unity in the universe cries out for simple, principled explanations.

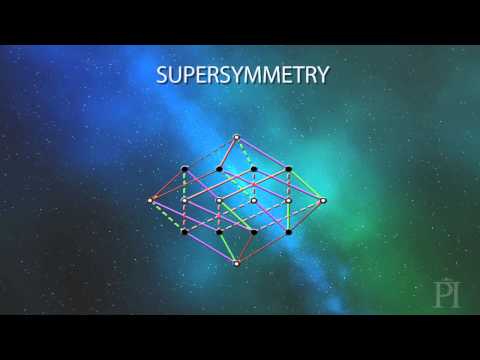

The popular theories like inflation and supersymmetry – which Stephen, like most others, went along with – remain unconvincing and lack compelling evidence in their favour. Physics now has, I believe, to return to the basic challenges and questions that Stephen posed in the earliest and most fruitful phase of his career. There isn’t a better place in the world for doing so than Perimeter. In many ways, we have taken on his scientific mission at a time when other places are either unable or have lost the confidence to do so. Stephen strongly supported the Centre for the Universe we have recently created here, kindly endorsing the Stephen Hawking Fellowship to which we hope to attract an extraordinary young cosmologist.

On Stephen’s very first night in Waterloo, I invited him and his team out to a local restaurant. We shared a lovely, memorable meal together. When I went to pay, I was told that a regular patron (who insisted on remaining anonymous) had settled our bill, as a welcome gift to Stephen. Stephen was delighted, telling me that, on all his travels, such a thing had never happened to him before.

One fine afternoon, during Stephen’s second visit to Perimeter, he and I decided to take a walk in the park behind the Institute. As we walked around Silver Lake by the public playground, a little boy started yelling, “That’s Stephen Hawking!” We thought no more about it, but the next day I received an email from the kid’s dad saying, “Was that really Stephen Hawking in the park?”

It turned out that the kid, although only six, had already read five of Stephen’s books. When he told his mom it was Stephen, she said “it can’t be!” But he desperately wanted to bring the books in and have them autographed. Stephen very graciously (and typically) agreed to meet the boy and thumbprint the books. The photo of the two of them together is one of my favourites. The thing I love about it most is that they’re both wearing the same shirt! Two little kids at heart, driven by curiosity and a desire to have fun making sense of the world.